Linux Malware

My last semester, I wanted to take advantage of one of the last opportunities I may have to take a truly challenging class. We learned the basics of reverse engineering, and for the final project my group and I wrote our own malware- including the client and C2 server as well as the implant- to target an ARM-based Linux raspberry pi.

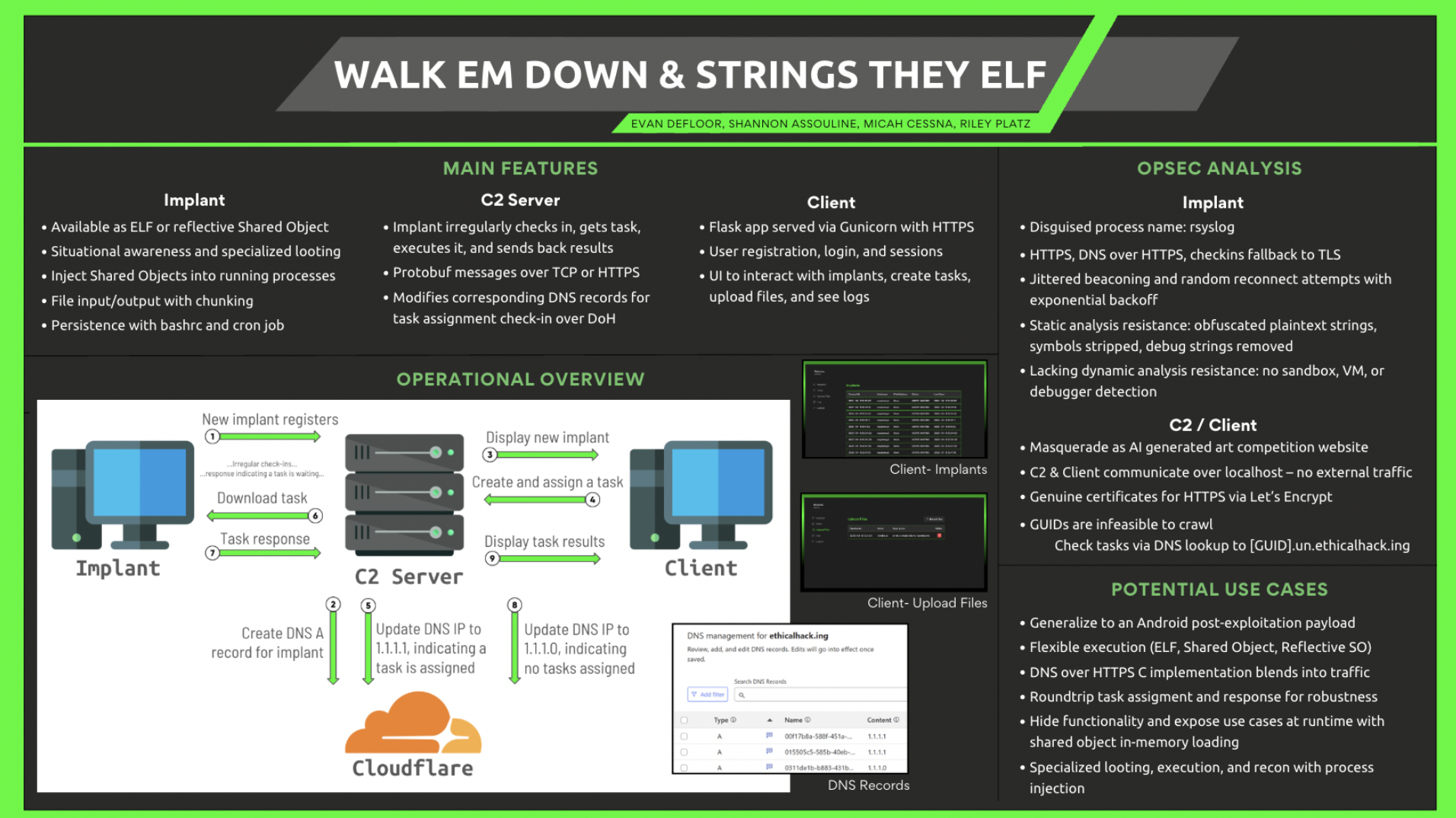

Our malware worked as follows:

Once our implant is successfully loaded onto our target, it calls out to our C2 over TLS to register itself and obtain an ID for future communications. Our C2 also creates a DNS record for each registered implant since we use DNS records as a task signaling channel. We built out a pretty feature-rich client UI to interact with the implant, which I now realize we didn’t take screenshots of, except for two tiny images on our poster shown below -_-. Nonetheless, once an implant is registered, it has its own webpage in the client where you can check its status, see basic info like hostname and ip, assign tasks, and receive results of tasks. Tasks included host awareness, arbitrary command execution, file i/o, process injection, and a kill switch.

Periodically with a jitter, our implant will make a DNS request over HTTPS to its unique DNS record in Cloudflare to check if there’s a task assigned to it; a record of 1.1.1.0 signals there are no waiting tasks while a record of 1.1.1.1 signals there is. We used DoH for check-ins to ensure our implant remained stealthy and blended in with other common network traffic. Only once the implant confirms there is a task will it make a request to a special C2 endpoint to retrieve it. The implant will then execute the task and return the response to the C2 which will store it so the Client can render the result.

Now I’ll go into slightly further implementation detail of various implant tasks.

Host awareness: We implemented our own versions of several CLI commands to ensure our implant remained stealthy on the host machine. This includes retrieving running processes by walking the proc table instead of using ps, and listing files in an open directory with dirent/opendir, etc.

Arbitrary command execution: The implant creates a child process which uses execve to run the command, and redirects stdout and stdin to the created pipe. The parent process receives the piped output and it’s then sent back to the C2 in a protobuf message.

File I/O: Our implant and C2 can chunk a large 1GB+ file and reliably transmit it and ensure proper reassembly without writing additional files or reading the whole file into memory.

Process Injection: Given a process name and a shared object to inject, our implant will attach to the target process, allocate memory for the shared object, then write it into the target process’s memory and execute dlopen on it. We find the pid of the process by walking the /proc table, and use it in calling ptrace to attach to the target process. We calculate the process’s mmap and dlopen locations. We wrote a function remote_call to find and overwrite the process’s current return address with a BRK instruction and overwrite the current registers with arguments for our command and the program counter pointing to our function address. When the process hits the breakpoint, we reset the return address and registers. We called remote_call with mmap and dlopen so we could write the path of the shared object into the victim process’s buffer and call dlopen.

The final environment and the exploit:

We were given the OVA of our final environment to reverse engineer and determine how to exploit. The environment was running a backup service which had two different processes that communicate via a Unix socket, one with no filesystem access but network access, and the child process with filesystem access but no network access. The HTTP server also allowed for runtime patches to be sent as shellcode, which essentially led to allowing for arbitrary shellcode execution in the environment.

I wasn’t really involved in developing the exploit mechanism, but my team created a reflective memfd payload to grab our implant from the C2 server via HTTPS, create a memfd buffer to write our implant to, and call dlopen to open our implant, as it’s available as a shared object.

Once in the environment, our malware’s goal was to exfilitrate the service’s stored messages. To do this, we listened on a socket in a parent process and used ptrace to run a shared object in the child process to open another socket and connect it, and then send the file descriptor for each file in the messages directory. The parent process receives these file descriptors, copies its contents to a buffer, and then sends them back to our C2.

This was absolutely the hardest class I’ve ever taken, and I’m so glad I did. It definitely felt like a pressure cooker at times, with so much to do in only a couple months and also being completely lost at several points. However, it definitely inspired some intense learning. At the end of the semester, we had a poster presentation session, and ours is below.

Thanks for reading!